One of the earliest and purest forms of Democracy in the United States took place at “town meetings”- a practice established in Massachusetts and distinct to the New England region. Unlike in our present-day use of “town halls”, qualified residents had the opportunity to not only discuss matters particular to their communities, but to actively vote on them- allowing them to have a strong voice in how their towns were administered.[note]Gott, Hollis M. “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy.” Arlington News, 16 Mar 1946, p.1. Accession number 1958.1.2, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 05 Jul 2017.[/note]

As part of my internship at the Arlington Historical Society, I recently had the opportunity of cataloguing twenty-six town meeting warrants for the Northwest Precinct of Cambridge- also known as Menotomy and present-day Arlington.[note]After a certain unknown year, the Northwest Precinct also came to include Charlestown. Please see: Medford Historical Society Papers. Vol. 14, p. 21. Medford, MA. 1911. Perseus Digital Library. 09 Aug 2017.[/note] The town warrants date between 1736 and 1795[note]Menotomy was part of the Northwest Precinct of Cambridge between 1732 and 1807. Please see: Ibid, p.21.[/note], covering a pivotal period from before to right after the American Revolution.[note]Notably, Elroy M. Avery, author of “A History of the United States and Its People”, said “Never was the town meeting more truly the voice of the popular will than in the gathering storm that ended in the war of American Independence.” Please see: Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.5.[/note] (See image above)

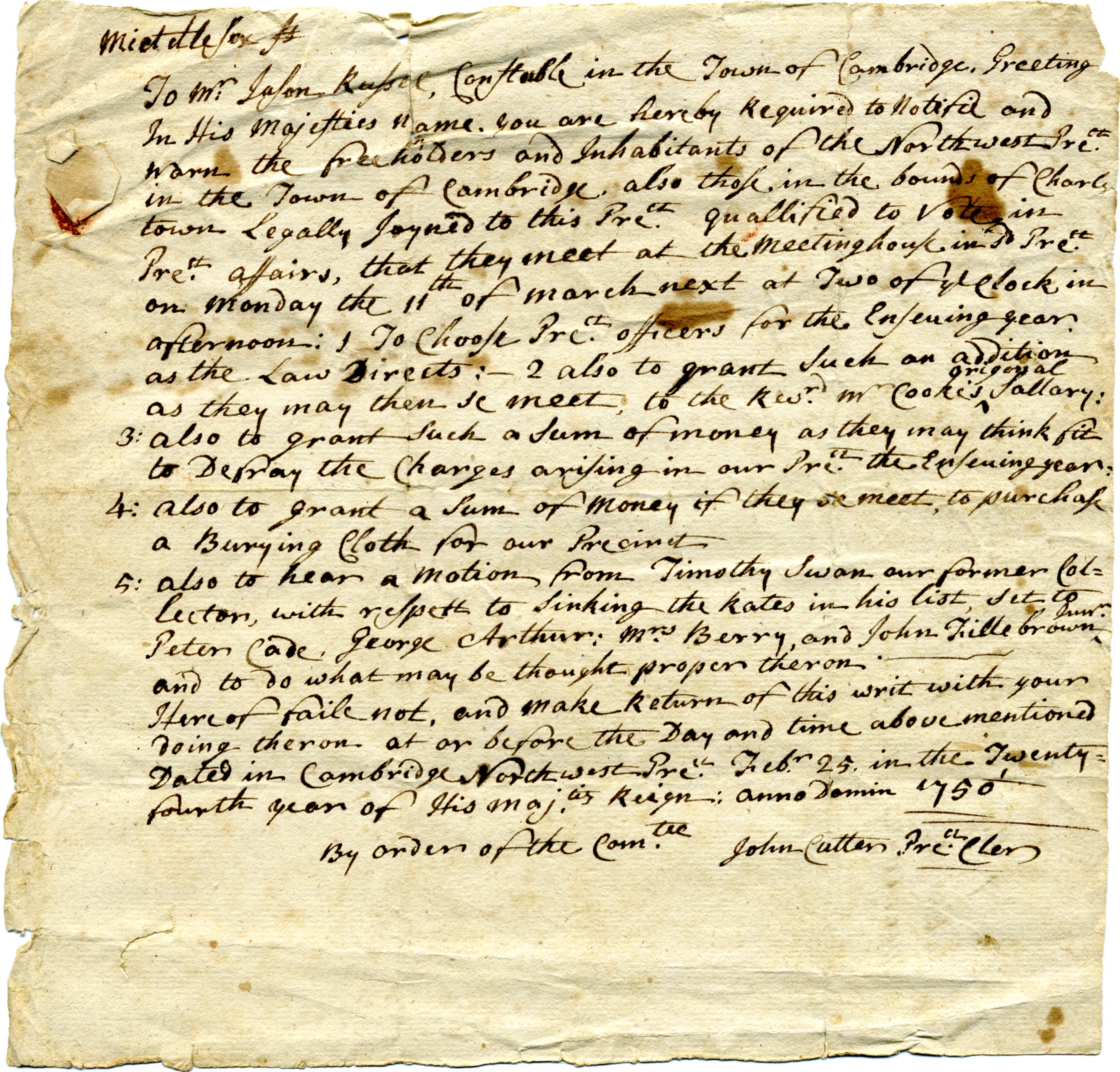

Only a few documents remain in good condition, and most have become yellow and fragile with the passage of time. Yet, they still have countless traces of those who handled them. There are creases along the center from when they were folded down and red residue on the corners from the wax used to seal them. Furthermore, even though the writing of the time was very stylized, one can see the difference between writers’ hands as well as their own take on spelling and abbreviating certain words. These details make working with first-hand evidence truly a privilege, because even the smallest of details allow us to take a glimpse back in time; in this case, the town warrants can teach us about what concerned Arlington during the colonial period and what occurred during town meetings.

What is a town meeting? Who was involved?

Excited to learn more about the town I call home, I became immersed in my task by researching names of town officials as well as customs of the time. Coincidentally, I learned that at the same time someone else was studying a document from the Society’s collections that described what town meetings entailed and what they meant to early American democracy. The document is an article written by Representative Hollis M. Gott titled “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy”; it was included in the Arlington News[note]The Arlington News was a local Arlington newspaper.[/note] on March 16, 1946. In this document, Gott tells us that the first town meeting may have been held in Salem, MA in 1629.[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.2.[/note]

He also tells us that, from the beginning, town meetings had “supreme control of the affairs of townships”, where the local government was run by the governed.[note]Ibid, p.1.[/note] Towns themselves were considered legal corporations and political units that were represented in the General Court; their role was such that it was considered more important than even that of the county.[note]Elson, Henry W. “History of the United States of America.” The MacMillan Company, New York, 1904. Chapter X p.210-216. Transcribed by Kathy Leigh. History of the USA, http://www.usahistory.info/colonial/government.html. 09 August 2017.[/note]

Generally, at a town meeting, “all the qualified inhabitants [met], [deliberated], [acted] and [voted]…”[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.1.[/note] Unfortunately, as might be expected of this period, “qualified inhabitants” meant only free adult males.[note]Elson, “History of the United States of America”, p.210-216.[/note]

Besides regular townsfolk, town meetings involved officials or “selectmen” such as a constable, prudential committeeman, clerk, treasurer, assessor, and collector.[note]Cutter’s History of the Town of Arlington also provides a list of others who were town officials (except constables), beginning from the year 1732. Please see: Cutter, Benjamin & William R. Cutter. History of the town of Arlington, Massachusetts: 1635-1870, p. 167. Boston: David Clapp and son, 1880. Perseus Digital Library. 09 Aug 2017.[/note] Most of which were likely voted for at a yearly town meeting as directed in many town warrants.[note]Town Meeting Warrant, 16 Feb 1741. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.12, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 23 May 2017.[/note] However, it is interesting to note that John Cutter appears as a committeeman for nearly thirty years (1736-1763) in the Northwest Precinct’s town warrants; this makes it likely that the position of committeeman may have run for a longer term.[note]Town Meeting Warrant, 10 May 1735. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.9, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 17 May 2017. & Town Meeting Warrant, 22 Feb 1763. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.24, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 06 Jun 2017.[/note]

It is also worth noting that within the Northwest Precinct’s town warrants, the roles of constable and the committeeman are the ones mentioned most often. During this time, the role of the constable was as a volunteer “peace officer” elected by other leaders in the community.[note]“History of the Office of the Constable.” Massachusetts Constable’s Office, https://www.massachusettsconstablesoffice.org/history-of-the-constable. 09 August 2017.[/note] On the other hand, the committeeman had the “general power to superintend the concerns of the town”, which included implementing decisions made during town meetings.[note]“Office of Selectman.” Connecticut Council of Small Towns, http://www.ctcost.org/pages/CCST_Files/2015-5.pdf. 09 Aug 2017.[/note] Thus, we find that town warrants were written by the committeeman to the constable in order that he might warn residents about upcoming town meetings.

What happened during a town meeting?

Town meetings were typically held yearly, on March afternoons.[note]Some town meetings were held on different months and there were years that had more than one meeting. Please see: Town Meeting Warrants, 2017.FIC. SMB.01.G.01, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA.[/note] Although some meetings may have been held at schoolhouses or the courthouse,[note]Town Meeting Warrant, 05 Feb 1735. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.8, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 17 May 2017. & Town Meeting Warrant, 12 Mar 1795. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.34, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 28 Jun 2017.[/note] they most often took place at a centrally located meetinghouse that also functioned as the town parish.[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.2.[/note] The original meetinghouse of Menotomy was known as the Second Parish, and it was located where the current First Parish Unitarian Universalist of Arlington stands- at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Pleasant Street.[note]The name changed once Menotomy became part of West Cambridge in 1807, before finally becoming Arlington in 1867. “Menotomy Minuteman Historical Trail: A Walking Tour of Arlington’s Past.” Menotomy Trail, p.7, http://www.menotomytrail.com/MenotomyMinutemanTrailGuide2.pdf. 09 Aug 2017.[/note] While we have little visual information of what it looked like, it was likely small and of simple wood construction, with minimal ornamentation.[note]“Religion in Colonial America: Trends, Regulations, and Beliefs.” Facing History and Ourselves, https://www.facinghistory.org/nobigotry/religion-colonial-america-trends-regulations-and-beliefs. 09 Aug 2017.[/note] (See image to the right for an example of a meetinghouse)

At the meeting, those in attendance would typically be called to order by the town clerk. After prayer by the minister, someone in attendance would read the articles up for consideration and they would all select a moderator for the rest of the meeting.

In earlier days, inhabitants voted by shouting “aye” or “nay”, but they later incorporated paper ballots.[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.3.[/note] Amongst the topics discussed were approving budgets and laws, voting for town and school officials, paying for the salary of a preacher, and repairing the meetinghouse.[note]Town Meeting Warrants, 2017.FIC. SMB.01.G.01. Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA.[/note] Although, in reality, almost anything concerning the town could be discussed.[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.3.[/note]

Attendance and respectful participation were expected: “No one could speak without the moderator’s permission, and he could impose fines for disorderly conduct”. However, those who did not attend also received fines.[note]Ibid, p.3.[/note] (See image below for an example of a town meeting)

Church and State

From the above evidence, it is clear that the colonial era was a time when the combination of church and state was acceptable. The church was at the heart of most colonial communities and religious observance was enforced, especially on the Sabbath.[note]“Religion in Colonial America: Trends, Regulations, and Beliefs”[/note] In accordance, one of the requirements to be considered an “inhabitant” was that one had to be a member of the Congregational church. Others, such as Baptists and Antipedobaptists, were not allowed to participate in town meetings.[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.2.[/note]

Thus, we find that the town voted for both church reparations as well as church officials and as such, they kept church and town records together.[note]Ibid, p.2.[/note] The Northwest Precinct’s town warrants specifically mention the need for reparations at the meetinghouse that included pews, a bell, and a pulpit. In addition, the salary of Reverend Samuel Cooke was brought up as a matter for discussion multiple times between the years 1747 and 1777.[note]Town Meeting Warrant, 16 Feb 1747. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.15, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 23 May 2017. & Town Meeting Warrant, 1777. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.28, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 13 Jun 2017.[/note]

Although, Representative Gott states that by 1725 towns could separate church and state, Menotomy continues to combine both secular and religious matters at least as far as 1789.[note]Gott, “Town Meeting’s Place in American Democracy,” p.2. & Town Meeting Warrant, 1788. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.33, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 28 Jun 2017.[/note]

Town Meetings Today

In retrospect, it is clear that town meetings such as these were only possible because they took place at a time when the concerns of towns were simple and populations were small. It was in later years, as the activities of towns began to expand and populations grew, that electing representatives became necessary. From then on, town meetings evolved into the current form of a “limited or representative town meeting”. Arlington began to make use of this type of town meeting beginning in 1920.[note]Ibid, p.6.[/note]

Although the “old” town meeting was not actually perfect and it had to change, we cannot ignore the great influence that it had on democracy in the United States. Thomas Jefferson was noted as saying, “New England townships have proved themselves the wisest invention ever devised by the wit of man for the perfect exercise of self-government and for its preservation.”[note]Ibid, p.1.[/note]

Possible Discovery: Was Jason Russell a constable?

Amongst the many constables mentioned within the Northwest Precinct’s town warrants there is one named Jason Russell.[note]Town Meeting Warrant, 25 Feb 1750. SMB.01.G.01, Accession Number 2017.FIC.21, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 06 Jun 2017.[/note]

A Jason Russell lived in the colonial house currently operated as a museum by the Arlington Historical Society. Although not much is known about his civic participation, we do know that he was a farmer and had many children.[note]Please see “Jason Russell and His House in Menotomy” by Nylander for background information on Jason Russell.[/note] He is also perhaps best known for his participation and unfortunate death during the Revolutionary battle of April 19, 1775.[note]Brorson, Stuart. “Stories of Arlington’s Jason Russell House.” Wicked Local, 23 Feb 2012, http://www.wickedlocal.com/x1793846760/Stories-of-Arlingtons-Jason-Russell-House. 09 Aug 2017.[/note]

While it was common for family members to have been named similarly to each other, the date of the document in which a “Jason Russell” is mentioned coincides with the time during which this particular Jason Russell lived (1717-1775).[note]On the other hand, his son also named Jason Russell was born in 1741 and was likely not a constable at the age of 10. Please see: “Jason Russell.” Geni, 04 Mar 2017, https://www.geni.com/people/Jason-Russell/6000000001657781052. 09 Aug 2017.[/note] (See first two images below)

Another clue is that the signature on the town warrant exactly matches another “Jason Russell” signature on the copy of a deed within the Society’s collections. The deed is for a lot in Mason, New Hampshire from Jason Russell to his son.[note]Copy of a deed to a lot in Mason, NH. Shelf 3, Accession Number 1931.18.1, Arlington Historical Society, Arlington, MA. 06 Dec 2008.[/note] (See last two images below) These two documents make it very likely that Jason Russell was a constable during the year 1750/1. Thus, this potential find may offer an exciting new insight to a man that was important to not only Arlington but also American history.[note]Cutter also notes a Jason Russell who was a prudential committeeman in 1761-63 and 1768 as well as a precinct assessor in 1758 and 1761-63. Please see: Cutter, “History of the town of Arlington,” p.167.[/note]

by Florentina G. Gutierrez, Collections Care Intern, Arlington Historical Society

Leave a Reply